If you’d rather listen to this essay in a browser or as a podcast, click the audio voiceover (“listen to post”) above. Read this if you need instructions on how to listen to episodes on your podcast app.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable, web-friendly version at ashleighellskells.substack.com, where all my other essays and podcasts live. You can request to follow me on Facebook here and Instagram here, and I’m happy to hear from you at aellsworthkeller@gmail.com.

For the first quarter-century of my life, Western North Carolina was the place that was the most special to me. Growing up in the piedmont of South Carolina, which was flat and hot and littered with pines and sand, the most anticipated event of my year was going up to the mountains. Summer camp was the center of it all, and by the time I was in high school, I was making the trip multiple times over the summer. I couldn’t stay away; it was where I wanted to be, and it held the people I wanted to be with.

And in the almost quarter-century since, in my ever-moving life of new experiences, it’s a comfort knowing that those rolling hills and valleys are there to stay. The faces may change, but those ancient mountains are one of those places you go back to and feel like it knows you in its bones, and you know it in yours.

I recognize this feeling. I know when I’ve got it, and I know when it’s not there. It’s why I know that Western North Carolina is one of the few places I can truly call home.

So Hurricane Helene’s immense devastation felt very personal. In the Appalachian region of Western North Carolina, East Tennessee, North Georgia, and Southwestern Virginia (as well as parts of Florida), the catchall of “devastation” meant exploded rivers, hundreds of thousands of toppled trees, homes and businesses washed away, and a landscape, culture, and people forever changed. I am grateful that everyone I know and love there is physically okay, but they—and their communities—will be recovering for a very, very long time.

It would be impossible to capture everything that happened in the years I spent here. My footprints are all over it, and in my mind, thousands of sense memories are bundled together, woven into beautiful touchpoints of childhood and young adulthood. I would not be me without this place.

It wasn’t until towards the end of my time there when I began to notice some of the downsides of the most rural areas—the signs of generational poverty, the occasional Confederate flag draped over a window, and segregation, decades-old, seeping into daily routines and churches and interactions. Not to mention the near-total erasure of indigenous communities in the entirety of this region, save for the sovereign nation (and town) of Cherokee, which feels like it must carry the entire responsibility of preserving that history.

At the time, I hoped for better. And I still do.

But the good of it is, of course, what makes it special to me. I’ve driven miles and miles on the Blue Ridge Parkway, stopping at vistas to admire the views, marveling at the tunnels carved into mountains, sung along with friends, windows down, as tangles of rhododendron fly by outside.

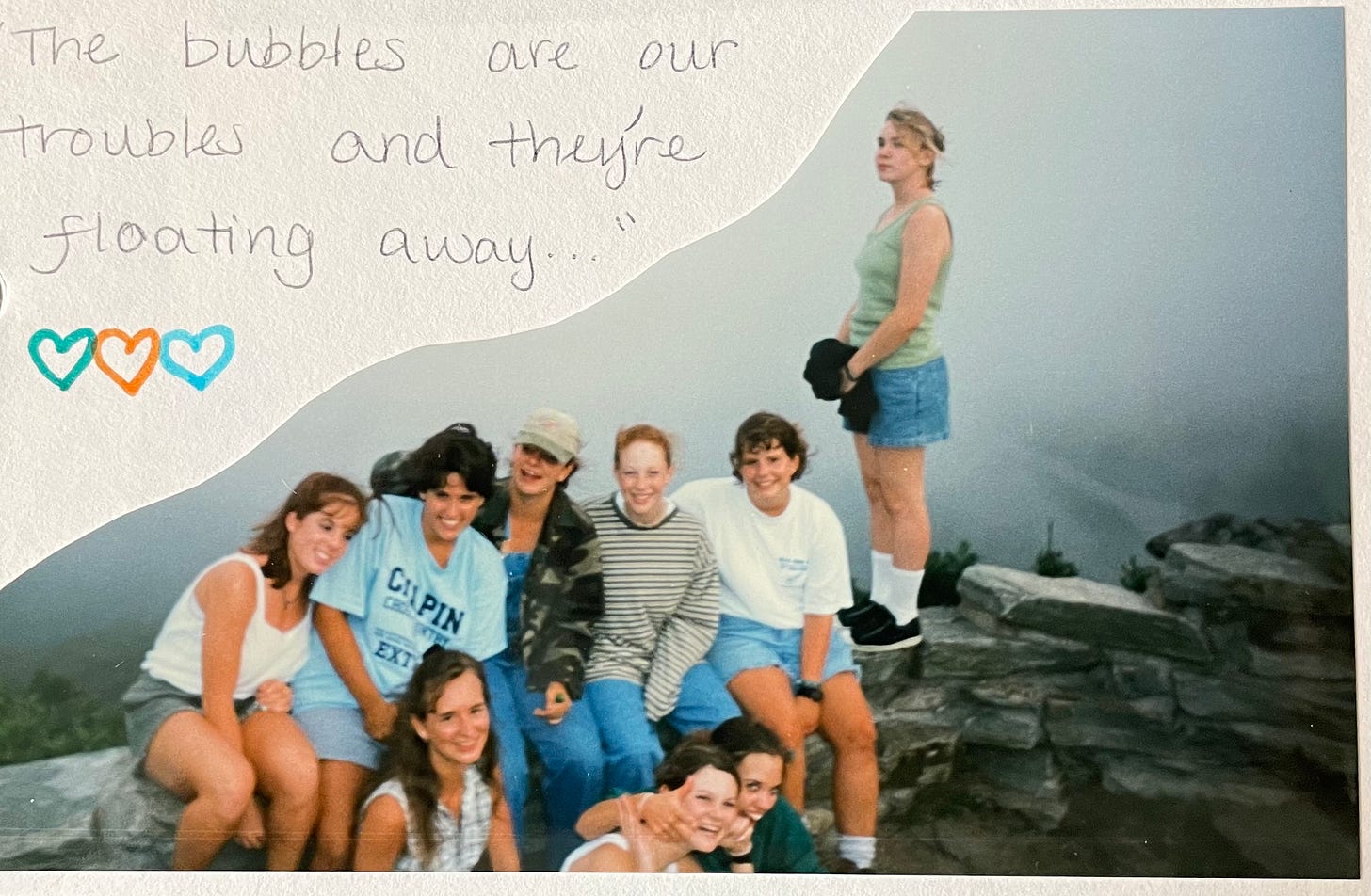

I’ve hiked Park and Parkway trails over and over again: Looking Glass Rock, Graveyard Fields and Falls, Craggy Dome and Gardens, Sam’s Knob; each excursion an imprint on my identity and on my connection to the nature surrounding me.

In the dark on the Parkway’s lookouts, I’ve whispered with girls and kissed boys and watched the stars swing across the sky, dreaming of the possibility of always being there, with the people I love, across so many lifetimes I couldn’t possibly live.

I’ve sloshed through creeks in the National and State Forests, Pisgah and Dupont, the water colder than I’d ever encountered, each time a mass of fifty kids walking a water’s mile to a rockslide or the falls, cold and wet and usually wondering why in god’s name were we doing this. (I don’t know. Character?) Ever since I was a middle schooler myself, I’ve had a love/hate relationship with the creekwalk. It was always a little bit miserable, slipping on rocks and beating up your shins, falling and pulling your friends down with you, but you learned to have fun with it, and rounding the bend and seeing the power of Looking Glass Falls greet you was enough of a reward, or so we were told. The mystery of what happens when you throw adolescent boys and girls into the damp woods together is that they kind of fall in love with it and with each other, steaming up a bus on the way home with their laughter and song, joyfully relieved by the notion that they’ll never, ever go on a creekwalk again. At least until next summer.

I’ve backpacked hundreds of miles of the Appalachian Trail on the spine of North Carolina and Tennessee, some of the same routes, over and over, sleeping in shelters or on the ground in tents, sometimes with one other person I love and sometimes with a group of rowdy kids (myself included). Thus far in life, I’ve found that nothing comes close to changing who you are in three days as a backpacking trip in the Appalachians.

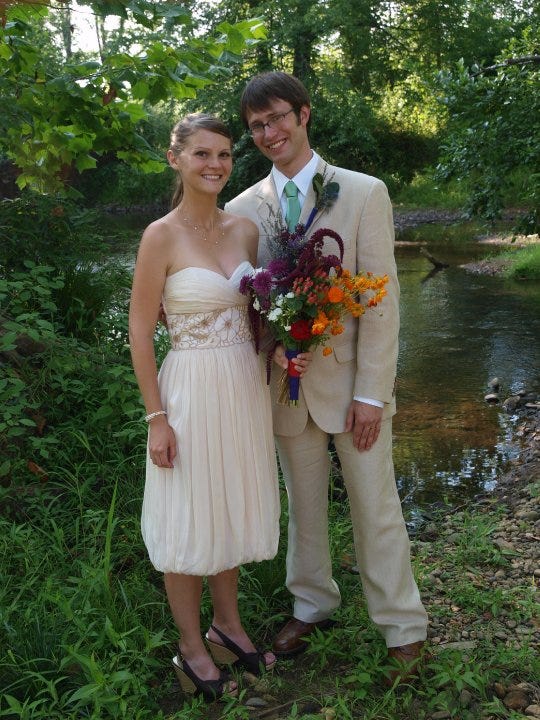

I’ve canoed the French Broad River, rafted the Pigeon (once) and the Nolichucky (many times), hiked over the Nantahala, and got married on the banks of the Swannanoa. Mountains may take all the glory, but the rivers have just as much authority in shaping both the land and the culture.

I’ve spent hours upon hours all over these hills, daydreaming, like when I was a teenager and saw a sign for the Blowing Rock Stage Company. It was then that I decided that my dream life would be living and working there. And I’ve had countless conversations with my best friends about a life like that, making plans to live there, all together, full of quaint, romantic dreams and hopes for a future that, some days, I still believe in.

There are dozens of summer camps sprinkled around Western North Carolina. I spent a summer on staff at Camp Lutherock, outside the small town of Newland, and every weekend was a trip into Boone on Highway 221 for Macado’s or Caribbean Cafe or to the little Boone Mall. We’d also take advantage of the many trails around the area and go out on group hikes or to natural rockslides and swimming holes nearby.

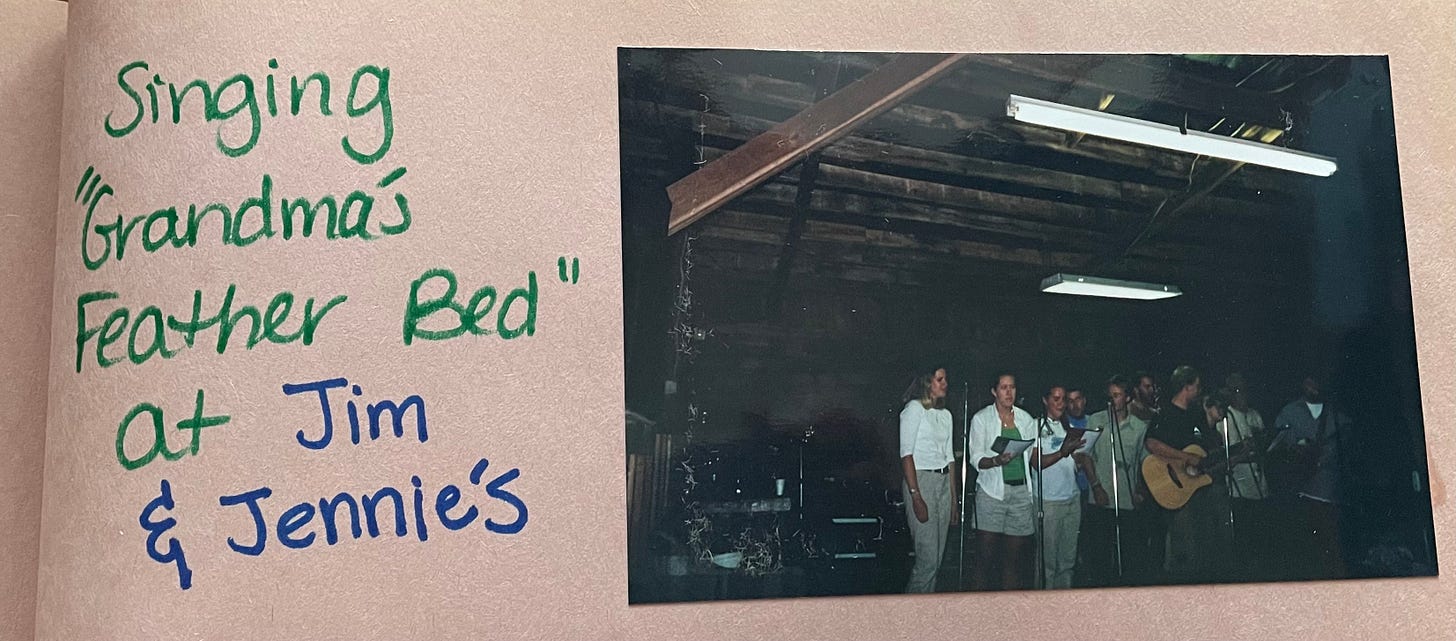

A favorite activity more than once a summer was to go out to Jim and Jennie’s Music Barn just down the road to hear some mountain music. One Saturday night, more than a dozen of us, almost the whole staff, came out, and it was someone’s idea to get up on stage and perform the classic song, “Grandma’s Feather Bed.” There was no alcohol allowed there—it was run by old timey folks, good Christian folks, and we were young, not-so-good Christian folks—and a few nameless people from our group snuck in some honest-to-goodness moonshine and were slugging it in the parking lot before our performance.

I thought we would get found out and kicked out, so I wasn’t happy about the moonshine nonsense (it all worked out). But I still fell in love with Bluegrass that summer and the rich culture surrounding it. I learned to separate Bluegrass from Country (a genre I’d shunned for many years, for reasons I don’t think I need to explain).

But Bluegrass was different, and cool people liked it! Mostly, though, I felt more of a connection to both its simplicity and its richness, and since then, its ability to situate my mind in a time and in a place that feels like it's a part of me.

Because it is. No matter where I’ve gone since, listening to Bluegrass always takes me back to those mountains.

And then there’s Asheville.

If you’ve been to Asheville, you know: it’s the funky hippie city, the home base that’s got it all, and, for a lot of us, the town that all other towns are measured by. And while the Ashevilliousness has gotten pretty out of control (spellcheck didn’t stop me on that one!), there’s a reason that it became what it is, the cool center of the Southeast’s universe, the magnet drawing me back as well as thousands of others who have ever spent time there.

Suffice it to say, the five summers I spent in Asheville would take a lot more than a couple of paragraphs to summarize. I got to be there in the late 90s/early 2000s, on the cusp of all of it, just before the outpricing, and before I was old enough to afford a mortgage. By the time all of that happened, it felt like a far-off dream to be able to make a life there. But I always wanted to get that part of me back; experiencing that world during my late teens and early twenties formed core pieces of who I am.

I worked at a camp called Lutheridge (more on all that in another essay, or a hundred of them). As camp counselors, we only got 23 hours off a week (it was definitely a work hard, play hard situation; still my favorite kind of situation) so we crammed a lot into that meager amount of time. Every Saturday afternoon, after moving our stuff to our next week’s area, packs of us would meet up at the flagpole or in front of Thornburg Hall and head out in a caravan of what felt like fifty cars. (I won’t even get into the tension surrounding the choice of who to spend your night out with, but let’s just say it was unnecessarily complicated and way too loaded).

First stop would be someplace like Wal-Mart, for shampoo or extra socks or some other kind of item you needed for the week. Then a trip to Diamond Brand, the comprehensive outdoor store located just down the road, which always had some kind of new gear we needed/wanted (and money was burning a hole in our pockets!).

Then dinner, which had to be a spot that could accommodate an enormous group, and the best nights were when twenty of us would crash Mellow Mushroom and eat so much pizza and revel at the groovy artwork adorning the walls. Other nights we’d roll over to the Chili’s close to Asheville Mall, or, in my later years, meet our fellow Senior Staffers at Barley’s or Bier Garden for some much-needed adult beverages (and even more needed adult conversation).

Some Saturday nights we’d make another stop, like head up to the Parkway and hang out and watch the stars, and to our 19-year-old selves, this was the kind of freedom that felt like a whole universe. There was a romance to those Saturday nights; all those possibilities, all that cash to spend (not much, but enough), all the camp gossip to share. And while the best night of the week for me was always Friday (Water Olympics! The dance! Sweet tea!), Saturday was the day of the week that moved the needle towards the people who would end up my lifelong friends, in a place that became dear to all of us.

With this routine, almost every weekend for five summers, you get to know a place. Downtown was where you wanted to be, and all the roaming hippies and the hacky sacks being tossed around and drum circles happening in that little park added a kind of mystique, and it was clear that any type of person was welcome here.

Most of us were tourists—Asheville Tourists—but, in time, we learned the lay of the land. It felt like home. I wanted it to be home.

There are more places with more memories, a roll call of little towns on peaks and in the foothills, and I’ve been to all of them, some dozens of times: Arden, Banner Elk, Beech Mountain, Black Mountain, Chimney Rock, Crossnore, Damascus (VA), Erwin (TN), Fletcher, Grandfather Mountain, Hendersonville, Hot Springs, Linville, Old Fort, Sugar Mountain, Swannanoa, Valle Crucis.

While they’re all different, they’re not really all that different. The towns—and the people who love them—live and breathe the mountains and the rivers. The people are there for the landscape around them, and it has been there for them, too. For beauty and faith and inspiration, for occupation, for life.

Until a hurricane stops and stays. When pushed by the wind and fed by so much rain, the land and the water will do what they do.

In spring 2019, after nearly 11 years in Vermont, I was hopeful that now was the time that my family and I could move back home. All of it hinged on getting a job offer first. As well as some positions in Arizona, I looked at Appalachian State in Boone and a few different non-profits in Asheville, and went through several interviews before being resoundingly rejected by all of them. I definitely cried about that. Moving to Western North Carolina just wasn’t in the cards for me. At least not then.

Because I’m not there, because I am not dealing directly with the loss of a house or of a town or of a life, I can sit here on my couch and write about it, and that, in itself, feels like an enormous privilege. Other than donating what I can and continuing to check on local friends who face a long-term recovery, the best thing I can do is try to keep this on people’s minds. I feel a little less helpless when I put the energy of story out in the world.

I have to wonder, though, a year from now, will the general public want to give to a cause that is “old news”? This recovery will need ongoing support. Consider becoming a sustaining donor to many of the relief organizations operating in the area. I know you’ve seen so many, but here are a few that I can personally vouch for:

Asheville-Buncombe Community Christian Ministry (ABCCM)

Community Foundation of Western North Carolina

Want to contribute in other ways? Here is a list of Asheville-based artists, businesses, restaurants, and non-profits that you can donate to or purchase from from afar. There’s a ton of cool stuff for all budgets, and everything given supports the area’s recovery.

While a lot of fall plans in the area have had to be cancelled, the message of “Come back next year,” gives me hope. Until then, sending love and financial support can show our friends that we won’t forget about them. We know that the people and the land around them are intertwined. The beautiful rolling hills and mountains and rivers and creeks and streams are the veins and arteries and blood of the place, the body, the spirit. And nothing can diminish that.

Reflection questions

What feelings have arisen in you when something happens in a place you love but you’re not there? What did you do about it?

Who are the people who feel like home to you? Have you talked to them lately, and if not, why not?

Western North Carolina is home to just one state-recognized tribe, the Tsalaguwetiyi (Cherokee, East). But there are several other tribes throughout the region, including (but not limited to): S’atsoyaha (Yuchi), Miccosukee, Mánu: Yį Įsuwą (Catawba), Cheraw, Yesan (Tutelo), Moneton, Keyauwee, and Shawandasse Tula (Shawanwaki/Shawnee).

The Western North Carolina region is quite large; as far as square mileage is concerned, it’s approximately the same size as the state of Massachusetts. Because of this, this is likely not a complete list of all the tribes in the region (which also must include Eastern Tennessee). My apologies for any inadvertent omissions.

Image: Looking Glass Rock, as seen from the Blue Ridge Parkway. Photo by a nine-year-old me, 1989.